Yo Khalil,

Yo Khalil,

Just wanted to tell you that the last Mo' Rockin' project you sent me is killin'!

Your sound from the first moments of the CD is just soulful!!!

Much Success,

Nick Payton

Hey Khalil!!!

Thank you for one of the great musical evenings of my life and I go back 83 years and actually heard Rachmaninoff play his Paganini Variations in Philadelphia in the 30s...

Thanks again for a memorable musical experience...

Sid Heller

|

|

|

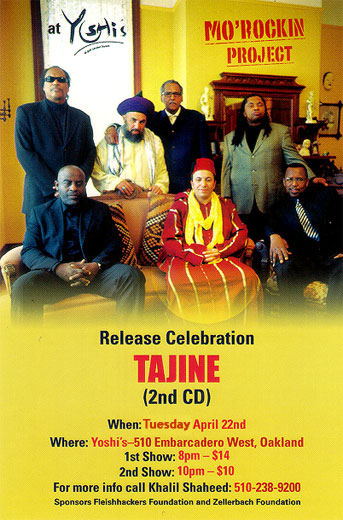

George Cables Benefit Concert

Saturday, December 8, Yoshi's in Oakland was the site of a benefit concert for jazz pianist and composer George Cables, who is recovering from organ transplant. The afternoon concert was sponsored by the Healdsburg Jazz Festival and other Bay Area organizations, and featured an all-star lineup of jazz musicians playing in tribute to Cables.

(Christian Kallen photo)Just wanted to tell you that the last Mo' Rockin' project you sent me is killin'!

|

|

Jazz fusion

One of the first acts on stage was the Oakland-based Mo' Rockin Project, an international community of musicians. From left, Richard Howells (sax), Khalil Shaheed (trumpet), Yassir Chadly (oud), and Bouchaib Abdelhadi. The group mixes North African sounds with North American jazz for a different flavor in fusion.

(Christian Kallen)Your sound from the first moments of the CD is just soulful!!!

|

Marshall Lamm

Marshall Lamm Productions

marshalllamm@earthlink.net

5/14/2007

To whom it may concern:

As publicist for Yoshis Jazz House I was introduced to Mo’Rockin Project a few months ago when they were booked to play the club. This band is one of the truest examples of fusion music that I have ever seen. The authenticity of the Moroccan instruments and vocals and the way they blend with the funky jazz quintet is truly fresh. The music has taken on a life of its’ own as the jazz players explore the North African melodies and the Moroccan’s merge in an effort to create a new and not only spiritual but fun music. This music should do well in dispelling some of the misconceptions people have about the Islamic Faith. I believe this music should be universally heard and supported. In these challenging times it is important to show just how well people with a common goal (to make good music), can work together. I know that Khalil, Yassir and the group are working on new material and I for one can’t wait to hear it. As a lover of great music and a socially conscious person I support Mo’Rockin Project and await there next move.

Sincerely,

Marshall Lamm

Morrocan-Born Musician Blends Faith with Jazz and Hip-Hop

By Carmel Wroth, October 21, 2006 10:14 AM

OAKLAND -- "Salam alaikum! Do you want to hear some jazz?" This was Moroccan immigrant Yassir Chadly's first introduction to American jazz.

A black Muslim security guard at San Francisco's Keystone Corner jazz club hailed him off the street with the characteristic Muslim greeting, and invited him to a new musical world.

The year was 1977 and Chadly had been in the U.S. less than a year, waiting tables and playing Moroccan music in a cafe. Growing up in Morocco, Chadly had only heard jazz in cartoons. When he heard the real thing, he became an instant fan. He started listening to the jazz greats like Art Blakey, Wynton Marsalis, and the Jazz Messengers, who frequented Keystone in the late 1970s.

Soon he was playing with Bay Area jazz musicians, and he developed a skill for mixing North African sounds with jazz. He has composed for the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater and performed with Phillip Glass.

In 1991 Chadly became the imam of an Oakland mosque, but he didn't stop making music. In fact, last year he co-founded a band, Mo' Rockin' Project, with jazz trumpeter Khalil Shaheen. Chadly said he wants his music to spread understanding and acceptance of Muslims and show audiences there's more to Muslim culture than fanaticism.

Chadly said he also makes music to counteract the puritanical voices of extremism that would restrict music.

As a child in Casablanca, Chadly would follow street musician around town learning the songs they played. He crafted his first musical instrument from a plastic gas can, a broomstick, and some fishing line. Soon he mastered several traditional North African instruments, including the Arabic lute, or oud, the African fretless banjo, and the gimbri, the bass lute of the Gnawa tribes.

When he first started to appreciate jazz, Chadly's only reservation was that the melodies tended to be European in origin. He felt jazz could use the spice of North African melody. He said he wanted to "dive into the jazz ocean and bring up to the surface these melodies."

On Mo' Rockin' Project's new CD, Sahaba, Shaheen's bright trumpet sound glides into an exotic backdrop of Chadly's throaty Arabic vocals, and melodic strumming. In one track, Muslim rapper Tyson offers a spoken word interlude: "I swim in an ocean of sound…from the shores of Morocco, to the streets that gave birth to the jazz and funk of Oaktown." Another track explodes with piano and drums and then resonates with the eerie cry of the Muslim call to prayer.

Chadly said the Muslim extremists teach that all kinds of music are bad for the soul, and try to ban it. As a tolerant Sufi Muslim, he objects to people who try to impose their own views on everyone around them.

"Extremists are like people who like hot sauce," he said. "They want everyone else to put hot sauce on their food also."

Chadly came to his role as a Muslim religious leader through another American pastime popular in San Francisco: the spiritual quest. Living in the Haight-Ashbury, he enjoyed what he calls "the cafeteria of spirituality." As he studied with Hindu gurus and tried out Buddhist mantras, he said "there was always that part of myself that was knocking, saying ‘remember me?'"

Finally he listened to that call and returned to his childhood faith in the Sufi traditions of Islam. He said Sufism was satisfying to him because, like jazz, there's a little bit of everything in it.

Chadly explained that Naqshbandi, the name of his Sufi order, means to chisel the heart, to carve out imperfections so only God remains. He said music is the chiseling of sound to bring out beauty.

"Muslims who say music is forbidden they take ugliest examples to prove that it is bad for soul. In the end, they throw out the baby with bath water," he said.

Over the door of his mosque, on Martin Luther King Junior Way in Oakland, is a sign with the name of the mosque and the words, "where everyone is welcome." Chadly's mosque welcomes a diverse congregation, including many converts. In a broader sense, he hopes to convert Americans, not to his religion, but to an appreciation of the beauty of his culture, and the humanity of their Muslim compatriots.

http://journalism.berkeley.edu/ngno/stories/027652.html

Mo'Rockin bridges musical cultures

By Andrew Gilbert

TIMES CORRESPONDENT

It's a long, long way from Chicago to Casablanca, but Southside-raised trumpeter Khalil Shaheed and Moroccan-born multi-instrumentalist Yassir Chadly have created the perfect vehicle to bring their musical worlds together.

While Chadly grew up playing traditional string instruments such as the gimbri and the Arabic lute known as an oud, Shaheed started his career backing blues great Buddy Guy and hanging out with Jimi Hendrix. The Mo'Rockin Project reflects both of their musical upbringings, seamlessly weaving together nostalgic North African melodies, jazz improvisation and surging soul horn charts. The results, captured on the recent album "Sahaba," or Companions, on the Remarkable Current label, is one of the most powerfully realized cross-cultural collaborations in recent years.

"Both of us are diving into the melody itself, forgetting ourselves, just thinking about the melodies and how to work them out together," said Chadly, who will be performing Mo'Rockin material with a stripped-down version of the band this evening as part of Danville Livery's free Summer Nights at the Livery concert series.

The full Mo'Rockin septet, featuring pianist Glen Pearson, bassist Ron Belcher, drummer Deszon Claiborne, Bouchaib Abdelhadi on oud, violin and dumbek (frame drum), and powerhouse saxophonist Richard Howell, who also co-produced the album with Shaheed, performs Aug. 24 as part of the Downtown Berkeley Jazz Festival at Anna's Jazz Island (where Shaheed leads a regular, all-ages jam session on Mondays).

In many ways, Mo'Rockin fulfills a lifelong musical dream for Chadly. Growing up in Casablanca, he was weaned on traditional Moroccan music, which is woven in the fabric of everyday life. At just about any family gathering or social occasion, drums are hauled out to accompany call-and-response vocals as part of the celebration. Growing up in the 1960s, he also heard a good deal of European music on the radio while soaking up the sounds of the Beatles, Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd.

Even at an early age, though, he realized that while he could perform Western music on the oud, European musicians couldn't join him playing Moroccan melodies.

Chadly moved to the United States in 1977, and settled in the Berkeley area the following year, drawn to the region by its cultural diversity and open-minded atmosphere. As his musical reputation spread, he became a highly valued resource, hired to compose and perform Moroccan themes for Alonzo King's Lines Ballet and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

Not surprisingly, he's been most sought after in jazz circles, where he's recorded and performed with masters such as pianist/composer Randy Weston, saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, alto sax conceptualist Steve Coleman and most recently Cuban pianist Omar Sosa, playing on the albums "Sentir" and "Prietos." But it's only in Mo'Rockin that Chadly feels he's found a jazz artist willing and capable of fully engaging in an East/West meeting of minds.

"In the other projects, with Omar Sosa or Pharoah Sanders, I'm the decoration, like a raisin in their dish," Chadly said during a recent interview with Shaheed at an Indian cafe in Berkeley. "They're great musicians, but they don't have time to take my music and mix it together and bring out something new. But now it's different, I'm bringing something and Khalil's bringing something and we're cooking together. This time, Khalil and I were able to build a bridge."

Shaheed has been building bridges as a vital part of the Bay Area music scene for 40 years, performing and recording with giants in jazz, rock and R&B, from Taj Mahal and Jimi Hendrix to drummer Billy Higgins, trumpeter Woody Shaw, altoist John Handy and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson. Long interested in blending jazz and R&B with African musical forms and rhythms, he's gained respect as a producer, composer, bandleader and educator who founded the Oaktown Jazz Workshop in 1994, which provides an essential jazz education to young musicians.

The seeds for Mo'Rockin were planted when Chadly returned from a trip to his homeland with a head full of traditional melodies that he absorbed while growing up. The two East Bay residents started talking about using the themes as inspiration to compose and arrange material together. The Mo'Rockin Project was born when they recruited some of the region's finest musicians to join them.

"It really wasn't hard, since most of them had been playing with me in Big Belly Blues Band," Shaheed said, referring to the horn-laden 13-piece R&B ensemble he's led for years.

"I knew when we put this together that they were open enough and certainly masterful enough on their instruments to make this work."

Both men cite their Islamic faith when explaining that the music isn't an end in itself. Chadly, an associate professor at the Starr King School for the Ministry in Berkeley and an imam at the Masjid al-Iman mosque in Oakland, hopes that Mo'Rockin will help foster understanding of Islam as a faith that spreads love by fostering mental discipline. In providing an example of coexistence through Islamic-inspired music, Chadly is spreading a message intended as much for fellow Muslims as for non-Muslims.

"Our goal is not to show people religion, only that there is sincerity between us," he said, motioning to Shaheed. "We are sincere people that have love and respect for everyone. These musicians respect the discipline of the music itself, how the harmonies should go. That's important to show the youngsters, especially young Muslims who are being fed that music is haram, or forbidden, that there is no music in Islam. How are they going to grow up if they have that talent within them? They have to see elderly ones with gray hair playing, that you can bring your talent out and share it with people."

***************************************************************

Interview from Rasputins Music Magazine

Hailing from Oakland, trumpeter Khalil Shaheed has been a jazz fixture in the Bay Area for years now, as a trumpeter playing with his Big Belly Blues Band as well as numerous other situations, and as an educator bringing jazz to the inner city. Sidi Yassir Chadly likewise has been an important part of the Bay’s music scene as one of the most well known oud (Arabic lute) players and singers in the area. He’s also a man with a long pedigree of musical adventurousness, having collaborated with Pharaoh Sanders and Steve Coleman among others. Together they have created the Mo’Rockin Project, a boisterous, upbeat musical experience that seamlessly melds Moroccan music, jazz and R&B. Propelled by the passionate voices of Sidi Yassir and his longtime associate Bouchaib Abdelhadi, riding on a bed of Moroccan instruments and the smoking rhythm section of Ron Belcher on bass, Deszon Claiborne on drums and Glen Pearson on keys, the Mo’Rockin sound is filled out with big horn charts and adventurous soloing, courtesy of Shaheed and Richard Howell on saxophone. The meeting of middle-eastern music and jazz may conjure up images of Pharaoh Sanders playing with Gnawa musicians, the sober quiet musings of Anouar Brahem playing with Jan Garbarek or Dave Holland, or the fiery minor modes of Sonny Fortune playing with Rabih Abou-Khalil. Well, Mo’Rockin is like none of that. This is truly something new.

Tom Chandler: How did you two meet?

Khalil Shaheed: I actually met Yassir through a guy named Annas Cannon, whose the brains behind Remarkable Currents, which is a young Islamic hip-hop record company. We were friends and he called me in to do some horn parts on Yassir’s album. So we started kicking it, and for a couple of years we would get together once a week. He went back to Morocco and brought back all these traditional Moroccan melodies, cassettes with snippets of stuff his grandfather sang, stuff like that. He’s always loved jazz and played jazz, gigs and recordings with Steve Coleman, with Pharaoh Sanders. He’s always been looking to do some different kind of stuff. So we put this project together. On the jazz side of it, Richard Howell, Glen Pearson, Ron Belcher, those are all guys from the Big Belly Blues Band, we’ve been playing together for years. It was real easy to just switch gears and go in another direction.

That’s one thing I like about all the musicians that I’m involved with is that none of them are boxed in. Everybody wants to try new stuff, go in different directions. That was our main goal with this, and to show how different cultures can come together and make fun music and dispel some of the negative connotations about the Middle East. It’s all about what we can create together.

TC: You take a really different approach than any of the other jazz/middle eastern fusion projects, like Randy Weston, or Avishai Cohen or Pharaoh, which focus on the serious, meditative or trance aspects. This is much more like a party. There’s spirit too, but it’s really FUN music.

KS: Well, a lot of that comes out of the Big Belly thing. We’ve been playing R&B all our lives. To me, jazz music was originally for dancing! You want to make people feel good. It’s just another way of getting to that same vibe, taking a little different route. Using the traditional Moroccan instruments and those melodies and then twisting them around into something else.

Yassir Chadly: The essence of what we’re trying to do is to forget ourselves and enter the melody itself. Joy! It’s like James Brown, and the dancing. We want to have fun!

TC: Khalil, do you feel like you’re getting an education in Moroccan music?

KS: Oh, most definitely! Yassir and myself and Bouchaib, who’s an excellent singer, and he also plays oud and all the Moroccan drumming on the album, we’ve done some trio stuff, with me on flugelhorn, and it’s a lesson for me every time I get with them. Their concept of time is different. It’s so much more organic than ours, more with the heartbeat. Learning those quartertones is really cool, man! I really enjoy it. It’s a challenge to play these melodies correctly, the way that they play them. To play them on the trumpet, you just bend it. I’m having a ball.

TC: And Yassir, has it opened new doors for you, what Khalil brings to it?

YC: What’s special about him, there is one ingredient that I don’t find with other jazz musicians: Patience! The others, they don’t have the patience to go through the melodies and learn. They have so much material themselves that they want to deliver, so when I play my stuff and they play their stuff, we have to have a break where the drum fades away, I do my thing, then I fade away and they come in. It’s not a real marriage. Whereas Khalil is trying to make that marriage happen.

TC: How does it happen? Does Yassir bring the tunes and then you start jamming on them?

KS: He brought the tunes… Having played a lot of jazz, he has a lot of distinct ideas. So he would bring the tunes and his ideas and we’d add my ideas and then structure them in a way that would be transferable to a quintet with Moroccan instruments. So it was an organic process. As we’d rehearse, there are great musicians in this band, and they all had input, to make it a collective project.

YC: Khalil and I worked one-on-one first. I said here’s a melody I have. I play if for him, he copies on trumpet, until he gets the melody. When he gets it, then we introduce the meter. He tapes it, takes it home, works with it, brings it back and says “OK, here is what I can add to it.” When I think about which melodies to give to him, I think about something that can turn from Moroccan to jazz.

TC: What’s the secret?

YC: I pretend I am a jazz musician! I put myself in their shoes. I say, OK, if I play this melody, how can I make this into jazz. And then I tell Khalil, “I like it when it’s like this.” And he listens and says if he likes it too. And we work from there. Once we fix the song then we share it with the others.

TC: Yassir, besides the notes that fall through the cracks, what are the challenges of playing with jazz musicians?

YC: The rhythm! For me, jazz rhythm is easy. The one is right here! But for them to feel my rhythm, they play some solos, when I come back, I come back on a different one then they have. For me, nothing is broken, but for them, everything is broken! That’s not where the one should be! So when we have solos, they have to hint for me, this is where our one is! (laughs) But in Moroccan music, I can enter on another one, and we have no problem adjusting. So I’m working on changing that, bringing them to that point.

TC: Khalil, will this experience take you in a different direction as you write new music?

KS: It has! Just their influence, being around them, I have some new stuff I’m working on. There’s a lot! It’s a really rich cultural thing. I’m more aware of what’s going on in Morocco, and it makes me more interested in other parts of Africa.

TC: Where are you going with this band?

YC: As much as the door opens, we go in. It’s now in a baby situation, where you have to nurse it and change its diapers, burp it. I’m not going to Morocco this year to be with my parents. I’m staying this year, because we have shows to do.

***************************************************************************

|